- Home

- Daniel O'Connor

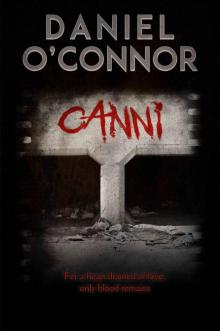

Canni

Canni Read online

Copyright © 2019 by Daniel O’Conner

All rights reserved

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, business organizations, places, events and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or locales is entirely coincidental.

Artwork by Andrej Bartulovic

Interior Layout by Lori Michelle

www.theauthorsalley.com

Printed in the United States of America

First Edition

Visit us on the web at:

www.bloodboundbooks.net

ALSO FROM BLOOD BOUND BOOKS:

400 Days of Oppression by Wrath James White

Habeas Corpse by Nikki Hopeman

Mother’s Boys by Daniel I. Russell

Fallow Ground by Michael James McFarland

The Sinner by K. Trap Jones

The Return by David A. Riley

Sons of the Pope by Daniel O’Connor

Yeitso by Scott M. Baker

The River Through the Trees by David Peak

They Don’t Check Out by Aaron Thomas Milstead

BleakWarrior by Alistair Rennie

Prince of Nightmares by John McNee

Body Art by Kristopher Triana

The Sinner by K. Trap Jones

Mercy by T. Fox Dunham

Monster Porn by KJ Moore

Pretty Pretty Princess by Shane McKenzie

Eyes of Doom by Raymond Little

The City by S.C. Mendes

Dark Waves by Simon Kearns

Cradle of the Dead by Roger Jackson

Loveless by Dev Jarrett

This book is dedicated to you.

FOR A HEART DRAINED OF LOVE, ONLY BLOOD REMAINS.

OWATONNA, MINNESOTA

Sterile.

It was all Wilk could think of as he captained the roaring Freightliner snow plow through the white-blanketed streets. People often asked him why he never got sick. They thought he’d be a prime candidate for pneumonia—up at 3:00 AM, out in constant sub-zero temperatures, clearing the roads while the commuters were still snug in their beds.

Yet, he couldn’t remember the last time he’d even had the sniffles.

He thought it was an old wives’ tale that the cold could give one a cold. The common cold was caused by viruses. That much he knew. He also refused to believe that viruses could flourish in this barren snow globe, where snot turned to icicle before the hanky left the pocket. It all just looked and felt so virginal. There weren’t even any smells.

Wilk thought back to when, as a child in winter, he’d held little wood frogs in his hand. They were frozen solid, like some unearthed Himalayan cavemen. He and his friends would return to their swampy habitat as spring approached, to watch the amphibians “come back to life”.

That is how cold his world was.

How sterile.

He bundled in layers. Serious layers. Thermal underwear, sweatshirt, sweater, hoodie, insulated jacket with high collar, three-hole balaclava over his face, hood on top of that.

Sticking out of all of that was the green and gold of a well-worn Minnesota North Stars cap. The NHL team had relocated to Dallas decades before, but they had seized his heart when he was young, and that is where they endured, like a first love.

He motored past the frozen skeleton of a structure called River Springs Water Park. He liked to recall bustling summer days when he’d taken his son and daughter for some fun in the sun. The park would live again come June.

But it was winter that paid his bills.

The plow fought its way through nearly three feet of fresh, white powder. The sound of the enormous scraper, combined with the rumbling of his 450 HP turbocharged engine, provided the bass and drum to some melody only in Wilk’s head. While his subconscious mind composed a song of the various sounds, he was lamenting the fact, as always, that his North Stars never got to hoist a Stanley Cup, when he hit it.

Thump.

“Okey-dokey,” he mumbled.

He could have blasted through, but he stopped the plow. The snow still came. Sideways. But, he was the type to do the right thing. He preached it to his kids, so he had to do it himself. He’d once hit a Siberian Husky, but he determined that the animal had previously died in the street and was covered over by the storm. He knew this because he dug it out and it was frozen as solid as those wood frogs. Usually, a thump was from some buried trash bags or other junk that had found its way into the path of his rig. He’d come across an old air conditioner, and even a broken office chair with a naked mannequin taped to the seat. Pranksters would sometimes bury things in the high snow just to fuck with the plow operators. He didn’t understand the pleasure of screwing with the working folk, but he couldn’t come to terms with a lot of things people did. He had once struck a hefty, snow-buried, Igloo cooler, still packed with cans of Surly Furious beer. He and his fellow plowmen divvied up the crimson-hued ale, but Wilk kept the cooler. Months later, he got stopped trying to lug the cooler, packed with sandwiches, snacks, and fruit drinks, into River Springs Water Park.

The sight of the bulky, clothing-layered Wilk descending from the truck cab might bring to mind an image of Neil Armstrong departing the lunar module. His first boot print in the snow was the only such impression for as far as the eye could see. He carried, not Armstrong’s Stars and Stripes, but a long-handled, steel snow shovel.

He trudged around to the front of the plow, vapor blasting through his mouth like a steam locomotive. With no idea what was buried in the snow, he employed his shovel with prudence.

No reason to damage the blade.

He cautiously lifted a few inches of snow and tossed it aside. Flakes attacked his eyes, circling in the wind like frantic gnats. Another couple of shovel scrapes and he hit it.

It was reasonably hard, yet felt moderately pliable. This was no air conditioner.

Time for some hand-digging. He knelt. His thick gloves brushed the powder aside, increasing in speed until he uncovered something. He could, initially, only see about a two-inch window of it.

Black. Maybe leather. He thought it might be a purse, or even a small suitcase. Further digging proved otherwise. It was a boot. Fancy women’s kind.

Worst of all, it was still on a foot.

Wilk dug like a hungry badger. Once he saw her leg, he quickly scurried over to uncover her head, in the faint hope that he might revive her.

That was before his digging revealed the frozen blood. Looked like someone had dropped a case of cherry snow cones. He furrowed past the first layer of red. There was her face. Seemed like she took pride in her manicured eyebrows, but the green eyes below them were wide as the Minnesota Plains, and her mouth was agape, filled with snow, and frozen in her final horror. Her left cheek was gone.

He removed one of his gloves. The frosty air bit at his skin. He felt her crimson-caked neck for a pulse, but only grasped the chafe of ice. He pressed harder, and his fingers penetrated a wound he hadn’t detected. It had been camouflaged by the frigid blanket of blood.

He mumbled the phrase he would utter to himself no matter if he had just been handed two nickels in change or, apparently, discovered an eviscerated corpse.

“Okey-dokey.”

Bill Smith’s plow had come from the other end of St. Paul Road. The two rigs faced each other, framing the body of the exhumed woman between their scrapers. Smith was so tall and lean that he didn’t appear to be the bulky Sasquatch that was Wilk, even with his own layers keeping him warm. Smith was Wilk’s most trusted ally. He was like an older brother.

“Oh ya, she’s a goner,” Smith said, as he knelt beside the body. Wilk stood behind him.

“You betcha,” replied his friend. “The police are on the way.

”

“Ya think maybe it was a bear or something?” asked Smith.

“Crossed my mind, don’tcha know. Didn’t see no tracks of any kind. Everything was all snowed over and such.”

Bill Smith had retired from a career in public relations, and just loved operating the plow. He had the oddball trait of being the only Boston Bruins fan that anyone around Owatonna knew. No one held it against him. Worse was probably the fact that he had the exact name of a New York Islanders goalie who had been instrumental in denying the North Stars a Stanley Cup. The boys never let him live that down.

Smith stared down at the woman. Wilk coughed behind him.

Whatever, or whoever, did this, thought Smith, wanted her neck exposed.

There was no sign of a scarf, which she almost surely would have worn. It was probably covered over nearby. He couldn’t help but stare into her eyes. He pondered what image she may have taken to her grave. He didn’t want to contaminate the crime scene any further, so he decided to stand up and back away, but he couldn’t turn away from her green eyes. Something inside him, inexplicably, half-expected her to awaken. Pure nonsense, but it did cross his mind.

Bill Smith, as a child, had also played with the wood frogs. He’d seen things return from the “dead”. He was contemplating the frogs, most of which were brown, or tan, and how he had occasionally uncovered a green one. They were green as the gaze from this dead woman’s irises.

That was the final reflection he had before his lifelong buddy, Wilk, killed him.

LAKE ELSINORE, CALIFORNIA

The vibrant green of the dress was what struck her. That, and the fact that the alternating vertical lines of the painted garment did appear to be true black. But the green lines were much wider, and the color leaped from the lower half of the photograph.

Still, she had read that Claude Monet avoided true black in his work, preferring to create a similar color through the blending of others.

The crash course in Monet, and the painters of Impressionism in general, was undertaken because she was about to meet the nineteen-year-old daughter of her new beau for the first time. The girl was almost fanatical about art—and Monet in particular. Knowing a bit about him could be an ice-breaker for Anita Chuang.

She didn’t want to screw this relationship up the way she did her marriage. Twenty-five years down the drain. She was well-off enough; her relocated medical practice was doing fine. She could afford the finer things in life.

But there was a hole in her heart.

It felt like Edgar might be the one to fill it. It was important to make a positive impression on his daughter, Verde. She was the greatest joy in Edgar’s life, and Anita desperately wanted to connect with her.

The month of March in Lake Elsinore rarely prohibits leisurely outdoor activities, so the barbeque was fired up in the lush backyard. It was a perfect seventy-three degrees.

As the briquettes changed color on the rear patio, Anita put down the book on Claude Monet. It was the third one she’d read that week.

Her plan was to gently introduce Verde to some delicious vegan burgers, and to also share her love of classical music. Appreciating its joys was not much different than enjoying art-on-canvas. There was color in music, too. The attractive doctor removed her 180-gram vinyl edition of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s Symphony No. 41 in C Major from its rice paper sleeve, and placed it on her Rega P8 turntable, running a soft brush across its grooves. This particular version, by Herbert Von Karajan and the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, had always been her favorite. She loved that it was recorded in 1970, the year of her birth. This particular piece had a strength about it, almost a finality, that felt reassuring.

Doorbell.

Mozart filled the room, the barbeque grew hotter, and the burgers—painstakingly crafted from chickpeas, sweetcorn, and a host of seasonings—chilled in the fridge. The oven was still warm from her homemade buns—whisked together from flax egg, non-dairy milk, coconut oil, and pink Himalayan salt. Dr. Chuang carefully arranged the three art books on her table, hurriedly fixed her black hair for the umpteenth time, and scampered to greet her visitors.

“You can’t tell me this is not flesh. This is insane!” smiled Verde, as she swallowed Anita’s meatless creation.

“Told you,” laughed Edgar.

“Thank you, Verde. I’m glad you enjoy it. No meat at all. Promise,” replied Anita.

The music played softly from small B&W patio speakers wired to the main system. They were no match for the majesty of the Magnepan Tympani flat-panels that delivered the classics in the doctor’s living room, but they got the job done.

Anita noticed Verde’s head nodding a bit to the symphony.

“Rocking out to my Mozart, are you?” she chuckled.

“A little, yeah. It’s not the Foo Fighters, but I can see why you dig it.”

“Well, that’s nice to hear from someone your age.”

“She’s quite open-minded,” added Edgar.

“There aren’t too many teenagers with such a love for Claude Monet,” said Anita, as she poured more Cabernet Sauvignon for herself and Edgar. Verde’s glass was still full of Coke Zero.

“I’m almost twenty,” answered Verde.

“Still a teenager,” smiled her father.

“Well, Claude is the man,” said Verde. “I saw your books inside, Ms. Chuang—or should I call you Doctor?”

“Please call me Anita. When you come for an office visit, you can call me Doctor,” she smiled.

“Cool. Dad says you’re gonna give me my HPV shots.”

“If that’s what he wants—well, if that’s what you want.”

“Sweet.” She took another bite of her burger. After chewing, she added, “Yeah, keep all those viruses away from me, please. Freaking bird flu, ebola, all of that stuff.”

“You don’t have to be concerned with any of that,” said Anita.

“They said on the internet that all kinds of people in Africa have died from Ebola and then, like, came back from the dead. There’s some ABC News footage of it, too.”

“Oh, Verde,” said Edgar.

“Dad, I’ll show you the video on my phone.”

“It’s likely they were all near death, and presumed dead by non-professionals,” said Anita. “I promise you, none of them were dead. There may have been clinical death in some, but we have that every day, where we can sometimes revive people, if caught in time.”

“Some dude was being buried when he popped his butt up again.”

Anita laughed, “That was someone’s mistake. I wouldn’t want to be that doctor!”

“Right?” said Verde.

“The internet,” said Edgar, “is as terrible as it is wonderful.”

“Dad . . . ”

“It’s packed with bullies,” he said, “You should only know the things they have written to, and about, my daughter, Anita.”

“I’d say that’s more the fault of humanity, and a likely lack of parenting, than of the internet itself,” replied the doctor.

“Nailed it,” said Verde. “People are rude.”

“In those art books,” said Anita, switching topics to lighten the mood, “I found myself drawn to that painting of the lady in the green and black dress.”

Verde’s eyes darted up.

“Oh, for sure. The Woman in the Green Dress is what it’s called. That’s Camille!”

“Camille?”

“Monet’s wife. You haven’t read all of those books, have you?” she laughed, sipping her soda.

“You know, I think I spent most of the time looking at the photos of his paintings.”

“Then, they achieved his goal. They drew you in. Text be damned, Anita Chuang is gonna enjoy the art!”

They all laughed. The Berlin Philharmonic were kicking ass.

“In all honesty, and I do try to be honest, I’m not such a fan of all the water lilies. Seems a bit much for me . . . ”

“But . . . ”

“Wait a second,” laugh

ed Anita, “I really loved a lot of his work, but I can’t tell you how many water lily paintings of his I’ve looked at this week, and I never saw even one frog. Have you?”

Verde sat still for a moment.

“I . . . I never thought of that. He has hundreds of lily paintings. There must be a frog in there. Could appear to be just a smudge of paint, but surely there is one somewhere. Unless the presence of a frog might deter from the peacefulness of the work . . . ”

“The absence of frogs,” said Edgar, as he gulped his wine.

“What does it all mean?” giggled Anita, discerning the initial effects of her alcohol. “Who is up for the next round of veggie burgers?”

“It’s not about the meaning,” said Verde. “Monet said it was not necessary to understand, only to love. He wanted people to feel something from his work, not to read into it.”

“Wow. That’s nice,” said Anita. “I did feel things from a lot of it. Oh, I put some titles in my phone—hang on.”

She slid the screen door aside and entered the house. Edgar looked at his daughter.

“Do you like her?” he whispered.

“Yeah. She’s cool.”

“Did you want another round of burgers?” he asked.

“Oh, no. Can’t get fat. Internet bullies, you know.”

“The Parc Monceau Paris,” came the shout from inside. “That’s one of the better ones, to me.”

Anita appeared again as the sliding door squeaked. “I also liked—let me see . . . ” She looked down at her phone, “The Garden at Argenteuil!”

“Yes, the dahlias,” answered Verde. “So beautiful.”

“And I already mentioned the green dress.”

“A favorite of mine too,” said Verde, “She seems ready to go out and have a wonderful time—I mean Camille, in the painting. I often wonder where she was going, and what it was like to live then. I mean, in this country, that was the world of Abraham Lincoln. What was life like in Monet’s France?”

“American Civil War,” said her father. “Not a great time to be alive. As for France, weren’t they invading Mexico around that time? Talk about HPV shots—the list of deadly diseases back then was enormous. Am I right, Anita?”

Canni

Canni